Appalachian Ode

Youghland

On my dad's 59th birthday, we walked farther through the woods than we had in at least a year: the three of us, my brother, my dad and I. We patted and identified trees, picked up snake skins, feathers, rocks, and sticks off the ground. For a moment, I was a kid again, and we were in West Virginia somewhere, or maybe central Pennsylvania, holding up paper maps, my dad pointing out where the moss on the trees was, and what does that mean about where North is?

The woods, this time of year, are full of ripe mulberries and deer. I never quite liked the word “forest” to describe what I duck into at the end of long work days and meetings, when existing feels the smallest bit unbearable, because for me, the woods are just that: wood.

My dad walks through these woods and knows what trees are the softest, the best for carving, the hardest, the best for furniture, the best for house building, the best for starting fires, the best for feeding you, and the prettiest golden grain (mulberry). Black walnut, butternut, red oaks, silver maples, sugar maples, hemlocks, cherry, — he pats the barks of them all, deciding whether they are sick or healthy, whether they will live to be old or they are old enough already. This is how he gains his energy, he says, laying his hand flat against the trunks and inhaling with his eyes closed.

I relearn what the songs of buntings, grosbeaks, and orioles sound like. I forget every winter when they leave for their Southern homes. I know what trees they like best. Indigo buntings and Baltimore orioles prefer the large, bare, sick trees by the overlook, grosbeaks like the trees near the beaver dam, and orchard orioles love the big sycamores by the creek that dominate the wetland. This is the language of my childhood: spring peepers chirping in March, the rustling of a rat snake through the brush, training my ear to know the conversations of birds that do not care if I exist.

I care very deeply that they exist.

In Pittsburgh, we have three rivers, all names derived from the names the Natives originally gave to them. The Monongahela: Lenape for ‘high banks or bluffs, breaking off’. The Allegheny: from the Delaware for ‘best flowing river of the hills’ or ‘beautiful stream’. The Ohio: Seneca for ‘great or good river’. Today, these rivers are used for transporting coal, and in the early mornings, barges dot the water. It looks very different than it used to.

The life in these forests and rivers was decimated. The Native peoples were pushed out, murdered, and perished from new diseases. The settlers eradicated the native species of timber wolves, the American chestnut, Eastern cougar, woodland bison, Eastern elk, and the Eastern subspecies of the Peregrine Falcon and replaced them with coal mining and steel.

Most of Appalachia is firmly in coal country: when my great-great grandparents first moved to Kentucky and Cincinnati, they came for the coal jobs. The culture in Pittsburgh (the Paris of Appalachia) is different, because it was a part of the seam that runs between coal country and steel country. Beneath us, there is the largest coal bed in Appalachia, an outcrop of which forms the cliff of Mount Washington. Tourists today go there to see a view of downtown Pittsburgh’s skyline and the point between the city’s three rivers. Above ground, we turned that coal into steel.

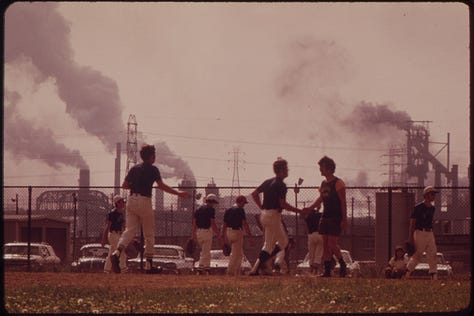

Pittsburgh steel built the world. It was our steel that won World War II, built the railways of the United States, the Eiffel tower, the Empire State Building, and the Panama Canal. There’s a strange sort of pride in Pittsburgh — I learned the process of how steel was made in my social studies class in the third grade. Now, most of our mills and mines are defunct, past industrial scars on the landscape. Interspersed between the booming tech, education, and healthcare structures that now fuel the city’s economy, There are slag heaps, coal pits, and bald mountains.

My family and I call our entire neck of the woods “Westsylvania” (Pennsyltucky always felt derogatory). Proposed during the early American Revolution as the name of the 14th colony of the United States, Westsylvania included modern-day southwestern Pennsylvania, all of West Virginia, and bits of Kentucky, Maryland, and Virginia. The name for the region has long been obsolete, but we like it because our half of the state isn’t like the Philadelphia half — we aren’t East coasters. The Youghiogheny, the river just outside of the city that flows into the Monongahela, gets its name from the Algonquin ‘contrary stream,’ as it flows uniquely North. That tiny part of the state, the area along the river and adjacent coal train tracks, we call “Youghland”.

I learned to skip stones on the Youghiogheny, barefoot in the river with tiny fish nibbling at my toes. I turned over rocks to find flatworms, salamanders, and crawdads, and painted with watercolors, while my dad stood in basketball shorts, waist deep in the water waiting for bass to bite. We baked the fish on rocks and fire with spices we brought from home and picked the flesh off bones while sitting on the sun-warmed riverbank.

Together, we watched eagles and herons fly over and sat in canoes with fishing rods, bags of Doritos, and boxes of strawberry Pop Tarts. It was never about the bass, it was more about the glitter in the bait, the pretty colors we used to pick out at the tackle shop with a giant shark head popping out of the sign above the door (we were so far from the sea).

All rivers lead to the ocean, but instead sometimes I like to imagine that all rivers lead home, to the dirty hollow where the wood ducks nest in the summers with the trail that heads back to my house without ever leaving the woods until just two blocks away from my front porch. It wasn't until I was accepted to graduate school that I began to read literature on ‘sense of place’. My place is in that river.

That river was the closest thing I had to an ocean. Like every ten-year-old in a landlocked city hundreds of miles from the coast, I briefly entertained the idea of becoming a marine biologist one day. But then again, becoming an ornithologist, microbiologist, epidemiologist, or meteorologist were all in the running for what would be my eventual degree. I was in the third grade when I first came across terms like “global warming”, “climate change”, “sea level rise”, and “ocean acidification”. I obsessed over phylogenetic trees, migration patterns, plastic pollution, coral bleaching, carbon emissions, and biodiversity loss. I brought dead bees into class, created posters about severe weather, and dissected owl pellets.

On my birthday one year, we combined the songbird migration with the Monarch butterfly migration south for the winter. Compared to birds, a butterfly’s lack of coordination stuns me. Every flap of their wings moves them in a different direction, and if they walked on land rather than flew, they might be stumbling on every step. How do these butterflies get anywhere? Every year, we chased something else up and down the Appalachians — the warbler and raptor migrations, the elk rut, the fall leaves. There was nothing I would rather do.

Steel Cities

Migration is a funny thing. When the continents split, the Appalachians lost pieces to what are now some of the mountains of Greenland, the Moroccan Atlas range, and the Scottish and Irish highlands. It was Scottish and Irish immigrants who migrated to Appalachia when they came to the United States (it was the Scottish who invented the term “hillbilly”). They were accompanied later by more immigrants from the Balkans, the Baltic states, and Russia. These groups were not able to get jobs on the East coast because they were seen as “other” and went West to the mountains for coal mining jobs and steel work.

While my Baltic and Russian family has been in the United States, we have only ever lived — interrupted by my dad for a brief period of two decades and change — in the Rust Belt and in Appalachia. I don’t know the cultures of my ancestors, or even my great grandparents; I do know steel and our rivers. My dad was born in Akron, Ohio, and moved to Cleveland soon after. His grandfather took him on early morning drives in Cleveland, across the Clark Avenue Bridge, to watch the mills and boats at Collision Bend. My great grandfather would smoke a pipe, shoot the shit with other fathers and grandfathers that brought their kids to this spot to watch the mills glow red in the dawn and play with other kids.

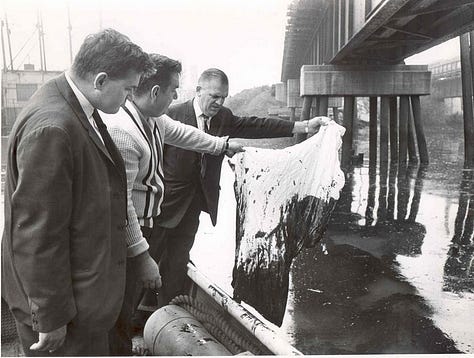

On June 22nd, 1969, while on their morning adventures, my great grandfather and my dad stood in front of the burning Cuyahoga River. That was not the first time that the river lit on fire (it had ignited 13 times before this point). With no regulations on water pollution, the steel mills dumped most of their waste into the river, creating what resembled an oil slick rather than a waterway. Cleveland and the Cuyahoga River quickly became the center of national attention, with outcry regarding the level of environmental pollution of the water and the surrounding area. The burning of that river (along with the very first Earth Day, that occurred that same year) led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Clean Water Act, and the creation of Cuyahoga National Recreation Area in 1974, which in 2000, the year of my birth, became Cuyahoga National Park.

While the Cuyahoga and Ohio rivers historically did not intersect, they now do, joined by the Erie Canal, also made from Pittsburgh steel. The Erie Canal proved that such a project was possible, and inspired the US to take over the project of the Panama Canal.

I visited the Panama Canal in the spring of 2024. Your entrance ticket comes with admission to a 45 minute documentary on the creation of the Canal called “A Land Divided, A World United”, narrated by Morgan Freeman. Freeman tells you that it’s one of the greatest engineering feats to have occurred in human history: building a canal through what used to be tropical mountains and forest to connect the Caribbean and the Pacific.

This massive effort was worth it, because we (the United States) connected the world by cutting Panama in half. The film focuses on the impressive scientific achievements of the canal, the story painted with a heavy hand of United States nationalism.

The 3D glasses hurt my eyes. Mosquitoes are only mentioned for a couple minutes or so during the movie. A giant mosquito on the screen buzzes in your face much like the actual bug might. Freeman tells you that this is when the vaccine for yellow fever was developed — another great scientific breakthrough to pair with the Canal.

What the film fails to mention is what the Panama Canal Museum dives into, with text-heavy plaques in both English and Spanish. When the French first attempted to build the canal in the late 1800s, it was estimated that 22,000 workers died from mosquito-borne illnesses like yellow fever and malaria, as well as injuries. When the US took over construction, they displaced thousands more people to create the “Canal Zone” in 1903. Five miles on either side of the Canal was designated American territory, housing those involved with the creation and construction of the canal.

Americans living in the Canal Zone called themselves “Zonians”. Society within the Zone ran on adapted versions of Jim Crow laws: workers on gold and silver tolls. Gold toll meant higher wages, better quality of life within the zone, and meant you were white or Northern European. Silver toll was reserved for Afro-Caribbeans and Southern Europeans, and meant doing more labor intensive work for less pay. Most of the workers that the US recruited for construction on the canal were from the Caribbean. Over 5,000 perished here too, from disease, accidents, malnourishment, and maltreatment. Years after protests and violent riots, the US finally signed a treaty to begin the transfer of control of the Canal to Panama in 1979.

The Zonians still meet yearly in Tampa.

It was Pittsburgh’s steel that built that canal, killed those people, and turned the land and lungs of the people in my city black. It’s what still gives us some of the highest asthma and lung cancer rates in the country, even with the EPA limiting the acceptable amount of pollution in the air and water.

Smokestacks spit out small dots of blue fire at night against a red sky. Mills smell like burning sulfur. Before the city power washed the buildings in the late 90s and early 2000’s, the buildings were black with soot. On high pollution mornings or evenings, our sky is hazy orange. Our riverbeds are covered in old cars and industrial waste. The water will make you sick. Trains full of coal in the valley by the river sound like home.

The steel mill in Braddock and cracker plant in Beaver County, just up the Ohio River from Pittsburgh, still pump toxic carcinogens into our air. Ethane crackers separate ethane from natural gas, and superheat it to "crack" the molecular bonds that hold it together and produce ethylene, which is then further processed into polyethylene nurdles, or plastic pellets. No, they do not teach us the steps of plastic production in grade school.

Funnily enough, cracker plants don’t smell like burning sulfur, but smell sweet from the mix of chemicals released into the air. I guess a factory producing actual edible crackers would also smell somewhat sweet.

Benzene is one of the main emissions released from cracker plants, and is a known human carcinogen that causes multiple blood disorders and cancers.

There are three elementary schools within a five-mile radius of the cracker plant.

Severe Weather

My Lyft driver to my morning class last month was a Trump supporter who asked me what I do for a living.

I smile and tell the driver that I’m an environmental social scientist, explaining that I study how people interact with science in different ways, from learning about science, to how scientists work with each other, with communities, and with policy-makers to make decisions, especially in the face of the climate crisis.

He’s confused. He wants to know if he can ask me something without me getting mad. I say yes, of course. To be curious is to be human.

He asks me if I really believe in climate change.

I pause, and think about how I should answer him. I tell the Lyft driver that I love Appalachia. My family and I were gone just about every weekend of my teenage years, hiking, camping, birdwatching, and fishing up and down the mountain range.

On one of those trips, I dragged a stick up and down a mountain, northeast of Asheville, North Carolina. I was annoyed that my dad insisted this hike was too hard, and that I needed to carry a hiking pole, or in this case, a stick from a nearby tree. To prove I was able to do the entire hike on my own, my stubborn-self dragged the stick behind me, up and down the entire mountain, down into the gorge, and back out, letting the stick’s bottom clank against every single rock on the trail behind me to voice my own disapproval.

When we talk about climate change, we frequently use the analogy of a frog in a boiling pot of water. The water slowly comes to a boil, and by the time the frog realizes that its surroundings are too hot, it’s too late. When I talk about climate change, I use the analogy of my childhood home in Appalachia.

The rain in early April of 2014 didn’t seem much different from any other hard rain we’d seen. In Pittsburgh, it rains; that’s a fact of life. We watched the news as Manhattan began to flood, as hurricane Sandy moved farther north and more inland than it ever was supposed to. In our little gray city, in our house with outdated plumbing, our pipes overflowed, and our basement filled with water and sewage. The whole house smelled like shit because it was shit.

We packed everything that was left and put it into a storage locker. We stayed at a hotel first. Then, I moved to a friend’s house, a massive mansion that had not one, but two staircases up to the second floor. I went to Cincinnati on a school trip that had been booked months in advance. I came back and my family moved into my mom's best friend's attic. Carrying our things up the four flights of steps in that house deteriorated my dad, and he walked with a cane after that.

We stopped traveling out of the city to hike in the Blue Ridge mountains of West Virginia, the rolling hills of Ohio, and the forests of Central Pennsylvania we’d visited so often before. I hated school. My grades declined. I’d always wanted to be a scientist, but for those years, I entertained just about any other idea. Classrooms felt suffocating, when I knew just a few hours away I could be sitting in an old-growth hemlock forest, listening to elk bugle for the fall rut.

As a fourteen year old, sucked into the world of my own problems at school with friends and my own mental turmoil, I didn’t grasp for many years that I lost my childhood home in Hurricane Sandy.

Six months later, my family’s move into a new apartment was easier without the stairs, but still exhausting. My mother filled my new bedroom with her plants and I slowly grew into that space, covering the walls with artifacts from our newly resumed travels around Appalachia.

In September of 2024, Appalachia was once again struck by a storm that was never meant to come this far from the sea — Hurricane Helene.

The scenes of destruction from Asheville, North Carolina and the surrounding area slowly began to unearth dead bodies, destroyed homes, and ruined livelihoods. I can’t possibly imagine what that mountain I dragged a stick all over, the places I grew up hiking, look like now.

My Lyft driver understands. He lived in Louisiana during Katrina, born and raised in the bayou.

I tell him I was 16 when Trump was first elected, two years after losing my home, attending an election party at Dave n’ Busters because we were sure that for the first time in United States history, a woman would win the presidency.

While Trump was president, I failed precalculus, graduated from high school, miraculously got into college to study psychology, and lived through the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic. Trump’s first presidency was like when I lost my house: I was a kid, and life went on.

I was working as a journalist when Biden was elected. I graduated from college. I published my first scientific paper. I got into graduate school, moved across the country to Arizona, set up my apartment with my mom and brother in the sweltering 117°F heat of August in the Sonoran Desert, and began my career as an environmental social scientist.

2025 began with the burning of Los Angeles. In the last few days of my winter break in Pittsburgh in early January, I spent most of my free time with my dad, watching the flames overtake house after house, watching as firefighting crews desperately tried to save the bits of communities they could. Large swaths of Appalachia still lay in ruin, but Hurricane Helene was forgotten about, as celebrities were quick to organize FireAid to rebuild their city.

I arrived back in Phoenix just as wind chills in Pittsburgh dipped below -10°F, in a historic polar vortex. It snowed in New Orleans. Phoenix, the world’s wettest desert, hadn’t seen rain in over 160 days.

The next weekend, when I drove north to the Grand Canyon with my best friend to stargaze, the air was a frigid 5°F as we gazed up at the Milky Way on Yavapai Point, wearing two pairs of pants and two pairs of socks each to stay warm.

Two weeks later, record-high temperatures hit the United States for early February when —just days ago — the landscape was covered in more snow than it had seen in years. All of this severe weather occurred in just two months — from the beginning of the year, to a few weeks after Trump took office.

I didn’t watch the inauguration in 2025. I spent my day hiking West Fork in Sedona, marveling at the icicles hanging from the red rocks and massive pine trees swaying in the wind.

In the months since Trump has been elected, I have found no comfort in the conversations in classrooms, labs, and meetings: the questioning of “where did we go wrong?” and “how did we fail to reach the other side?” I feel a bit like the frog boiling in the pot (or maybe Sisyphus), collaboratively making spreadsheets of the words that are now censored in grants, and deciding on what other words to substitute in.

So yes, I tell my Lyft driver, I do believe in climate change. I don’t need data on carbon emissions, severe weather, melting ice caps, and rising temperatures to prove that it exists — I’ve lived it. I’ve seen it rip apart people’s lives. I’ve had it rip apart my life and I’ve had to keep on living.

The Lyft ride ends. My driver turns around in his seat and tells me thank you for sharing my story with him. I get out of the car, reflecting on our conversation.

The truth is, we know exactly where we failed: we tried to remove humanity from our science, when to do science is to be human. Curiosity is human nature, as is wanting to connect with others and share our stories. Connecting with others is the reason we have become so successful as a species.

Scientists are told to be objective. It’s a large part of our training — to learn how to conduct science without emotions, advocacy or personal opinions.

I can’t remain neutral.

I am not a scientist or a person who will sit quietly while I watch my country burn and flood, and its people suffer. I’m sharing this story so you know why I’m here, and who I am both within, and outside of my science. That will be how we navigate our way forward: by being human, and connecting with others as people, not as scientists.